Catherine Murphy TD has done the nation much service in her time in the Dáil. Her most recent efforts to extract information from the State apparatus may have as great an impact as anything she has done.

The Social Democrats leader set down a series of Parliamentary questions, asking Ministers if they were aware of the CJEU’s recent Bara judgment and if their Departments had undertaken any database building projects which were effected by it.

(Here’s a snappy explainer on the Bara Judgment and how it limits government database building)

It turns out that the Ministers are working on plenty of databases, spread across the State’s various Ministries and agencies. (I’ve detailed some of these previously) However, what was most notable in the answers is that Ministers still do not want to change plans that the highest court in the EU have found to be illegal. No Minister said that their database projects were being halted.

Most concerning is that some, such as the Minister for Finance, appear to have received factually inaccurate legal advice as to the actual meaning and content of the Bara case.

Minister Noonan described the facts of the Bara case and why they did not apply to Revenue’s Local Property Tax Database;

The Bara judgement concerned the sharing between two state entities in Romania of data without legislative authority or consent from data subjects. On that basis the European Court of Justice found that the data sharing in question was illegal without notification to or consent from the data subjects.

Unlike the situation in the Bara case where there was no legislative basis for the transfer of the specific data, Section 151 of the Act explicitly states that Revenue can request ‘relevant persons’ to provide it with any information in their possession or control that may be required for the administration of LPT, including for the purposes of establishing and maintaining the Property Register. Section 153 also clearly sets out the entities that are considered to be ‘relevant persons’ for the purposes of LPT.

Revenue has confirmed to me that it is satisfied that all of the information sourced from the various ‘relevant persons’ was done in accordance with legislation. Therefore the Bara Judgment does not apply.

Whether the Local Property Tax Database is legitimate or not, this is simply an inaccurate description of the facts of the Bara case.

The Romanian government had, in fact, passed legislation to authorise the data sharing that was being challenged. The legislation is outlined in paragraphs 10-13 of the CJEU judgement itself under the subheading “Romanian Law”. The Irish Government has passed many similar laws here in recent years, from the Individual Health Identifiers Act to the rules governing the Primary Online Database. And, as the Minister explains in his answer, the Local Property Tax database was simlilarly built on such a legislative provision.

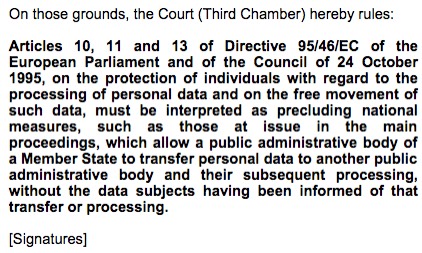

However, what the EU Court found was that national legislative provisions such as the Romanian (and, I would argue the Irish) government had passed to allow them to transfer citizens’ data between bodies were incompatible with the Data Rights of EU citizens and therefore illegal.

If the most powerful Minister in the Government is being given legal advice based on a significant misreading of CJEU caselaw, it does not bode well for the capacity of the State to demonstrate that they have not breached that law in their rush towards a database state.