Urgent questions for the Data Protection Commission.

A) Do you know that the United Nations Human Rights Council has deplored the failures of “Facebook” in connection with the facilitation of genocide by the Myanmar military in Rakhine district in Myanmar?

B) Do you not know that, under international criminal law, the commander of a military force is, in principal, responsible for the crimes of his forces?

C) Do you know that General Min Aung Hlaing, the commander of the Myanmar military forces (since 2011) communicated with his forces by means of, inter alia, the Facebook platform?

D) Do you know that General Min Aung Hlaing’s account with Facebook was established with Facebook Ireland Ltd. and that the law applicable to that account is Irish and EU law?

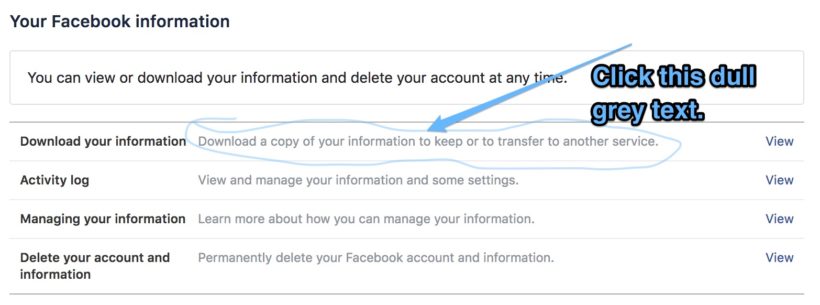

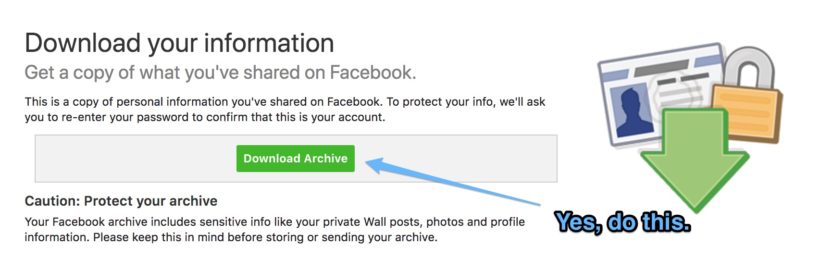

E) Do you know that Facebook Ireland Ltd., in or about 19th April 2018, purported to assign or transfer that account (and others) to Facebook Inc. in Menlo Park, California?

F) Do you know that the European Parliament has challenged the propriety of that assignment in paragraph 13 of a recent Resolution?

G) Do you know that any claims of individual Rohingya people for compensation for complicity by negligence or otherwise, if any, by Facebook Ireland Ltd., in the Myanmar genocide and other crimes for which General Min Aung Hlaing is responsible, can and should be brought in Ireland?

H) Do you know that the account records purportedly transferred by Facebook Ireland Ltd. to Facebook Inc. in or about 19th April 2018, are, in principle, evidence required in any criminal or civil claims brought against General Min Aung Hlaing or Facebook Ireland Ltd. arising from the Rohingya genocide and other crimes?

I) What steps, if any, does the Data Protection Commission intend to take to recover and secure, for the Rohingya people, that evidence, purportedly transferred by Facebook Ireland Ltd. to Facebook Inc. in or about 19th April 2018?